I want to spend this week talking about Italy. (We will return to France and Germany next week.)

Why Italy now?

There is a referendum coming up on Sunday December 4, the result of which is systemically important for the future of the Eurozone and perhaps even for the EU.

The Ballot--a bit of a mouthful--reads as follows:

Do you approve the text of the constitutional law concerning "Provisions for getting rid of equal bicameralism, reducing the number of MPs, containing the operating costs of the institutions, the abolition of the CNEL [the National Council of Economics and Labour--a consultative body] and the revision of Title V of Part II of the Constitution" approved by the Parliament and published in the Official Record n. 88 of April 15 2016.

What is likely to happen (Deutsche Bank's chart)?

And another

flow chart from Dansebank, which traces good and bad market outcomes.

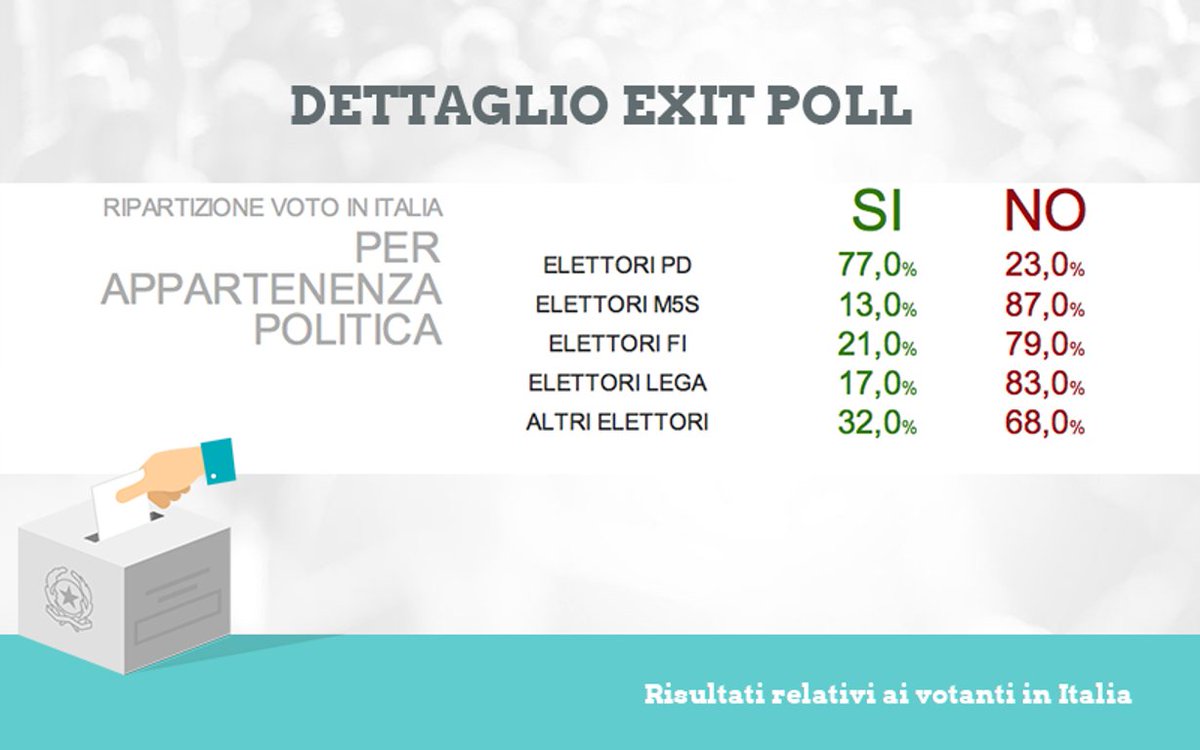

The reason why the referendum has a broader significance for the EU is that Renzi's fall is likely to boost the chances of M5S, a populist party with a dislike of the Euro and the EU.

The immediate context for this Referendum was set by the former Italian President Napolitano, who was instrumental in

the fall of the then Prime Minister Berlusconi in November 2011; the establishment of

the technocratic Mario Monti Government of 2011-2013; and the formation of

the Renzi Government in 2014.

The more profound context for this Referendum is Italy's economic problems: low growth; high unemployment--esp. youth unemployment--and

failing banks with

a very high level of bad loans ["

In Italy, 17% of banks’ loans are sour. That is nearly 10 times the level in the U.S., where, even at the worst of the 2008-09 financial crisis, it was only 5%. Among publicly traded banks in the eurozone, Italian lenders account for nearly half of total bad loans."]

Election Results 2013:

For details see

here

For a point of comparison with earlier elections see here and here

Recent Prime Minsters:

Silvio Berlusconi (Right): 1994–95; 2001–06; 2008–11

Romano Prodi (Left): 1996–98; 2006–08

Massimo D'Alema (Left): 1998-2000

Mario Monti (Technocrat); 2011-2013

Enrico Letta (Center-Left): 2013-2014

Matteo Renzi (Center-Left): 2014-???

The Referendum and Its Aftermath

The details of the referendum vote itself are less interesting than the implications of the yes and no vote.

Briefly stated, the referendum addresses a problem in the design of Italy's Upper House (the Senate), the current political make-up of which is as follows:

The Italian Senate is weird in all sorts of ways:

(i) It is elected only by voters above 25;

(ii) Senators must be 40 years of age or more (old farts basically);

(iii) 6 of its members are appointees for life rather than elected; and weirdest of all

(iv) it has equal power with the chamber of deputies (the lower house)--i.e. an example of perfect bicameralism. [This means: "

Any law can be initiated in either house, and must be approved in the same form by both houses. Additionally, a Government must have the consent of both to remain in office."]

The Italian Senate makes it more difficult for a government with a majority in the lower house to implement radical policy change.

There have been three earlier attempts at reforming the Senate--one in 1993, one in 1997, and another in 2006--all failed.

Renzi's referendum is designed to centralize power in the Lower House and make Italy easier to govern (or misgovern--depending on what you think of the government of the day.)

The difficulty in reforming the Constitution is a function of:

(i) Italy's history of fascism and a subsequent desire to disperse power and make it difficult for a strong leader or government to enforce their rule unchecked;

(ii) Italy's deep-seated conservativism--any change is bad; and

(iii) Italians reverence for their 1948 Constitution---a reverence that exceeds even that of Americans for their Constitution.

If this current Referendum succeeds, TWO major constitutional changes will occur:

1. Senate will shrink to 100 (from 315) and the current Senate will be replaced by a House of Regions and Municipalities with no veto over legislation coming from the lower house;

[To understand why many Italians want to reduce the number of their Politicians, see this graph:

2. The Central Government will gain competences at the expense of Local Governments (widely believed to be corrupt and spendthrift);

Indirectly--but only indirectly--the Referendum decision bears on a recent change in the electoral law (enacted in 2015)--the so-called ITALICUM--which took effect this year. This law gave a winning party a bump in seats in an effort to engineer a comfortable majority--a majority-assuring electoral system. The Constitutional Court is yet to rule on the legitimacy of this new electoral system.

--------

Rather unhelpfully, some Italian journalists view the Referendum largely in terms of this new electoral law. The Referendum itself, however, makes no direct reference to this or any electoral system, even if a NO vote is likely to take down the ITALICUM with it. In short, a YES vote is necessary but not sufficient to sustain the ITALICUM (the Court can always require changes); while a NO vote is probably (for political rather than legal reasons) sufficient to kill the ITALICUM.

As Cordogno (see below) puts it: "The electoral law is politically linked to the referendum, but it is de facto a different parliamentary process. The Constitutional Court will have to issue an opinion on the electoral law, which was supposed to happen on 4 October. However, on 19 September, it declared that any opinion will be postponed until after the referendum, both for technical reasons and to avoid any interference with the vote."

_____

From a more general political point of view, the campaign for a NO vote is being led by remnants of Berlusconi's party, M5S, the racist Northern League, and a bunch of failed hacks from the old left Bersani and D'Alema wings of the PD. A NO vote is likely to aid these factions at the expense of the modernizing Renzi wing of the PD.

Berlusconi is playing a particularly cynical game--he is backing NO, even while he himself proposed something similar as PM in 2006 and after initially supporting the proposed changes in 2014/2015. (Thanks to Richard Bellamy for clarifying some of this.)

Since M5S is potentially the party with the most to gain from a NO vote, the Referendum is bound up with the question--what do I think of Grillo and the M5S? Yet before we talk more about Grillo, it is worth noting a paradox here. Rather than thinking that a NO vote is good for Grillo, it is possible to also think that a NO vote would be very bad for him and his party. Consider the following scenario:

If the NO vote succeeds, it is thought that this will bring down the ITALICUM too (link in Italian, but the key bit is this: The scenario of a NO victory, paradoxically, may be more stabilizing. The constitutional status quo would require a radical overhaul of the ITALICUM electoral system...in a proportional way. In that case, the prospect of a winner-take-all victory for M5S would diminish.). Any post-NO electoral reform, in short, is likely to take Italy towards a more proportional representation system. This would likely yield weak central coalitions (think here of the Letta Government of 2013-2014) and would not be propitious to the M5S. Personally, I can't see how weak central coalitions are going to be of any help in enacting the reforms that Italy needs. Another reason to vote SI.

HOW DOES GRILLO'S M5S COMPARE TO TRUMPISM and FARAGISM?

There is

a tendency in the press to equate Grillo, Trump, and Farage (Marine Le Pen too)--all anti-establishment, anti-expert, and anti-globalization. There are some similarities. But there are also some important differences.

Take, for example,

this description of a composite supporter of Faragism/Trumpism:

the characteristics of people who backed Brexit closely match the characteristics of a group of voters that the polling organisation calls “authoritarian populists”. They are people who could broadly be described as out of step with the cultural assumptions – such as a respect for human rights, immigration, feminism and diversity – that are the bread-and-butter of liberal democracy.

From what we know of the Brexit/Trump voter, they tended to be older, less educated, and drawn from less cosmopolitan areas (rural rather than urban, drawn from the economically less successsful rather than more successful regions etc).

Neither the ideology of "authoritarian populism"nor this voting profile fits M5S.

Here are few points to bear in mind:

1. M5S draws support from the young more than the old and from the more successful rather than the less successful regions--very different from B/T voters. Indeed, as Nicola Maggini says of the Feb 2013 election:

"The youngest and the most dynamic sectors of Italian society seem to have chosen in these elections

the M5S."

2. Grillo reigns over the M5S--a party he founded in 2009 with an internet entrepreneur Roberto Cassaleggio (who died)--but leaves the rule of the party to others. The key figures are now such people as: Alessandro di Battista, Luigi di Maio; and now the two young female Mayors Appendino (Turin) and Raggi (Rome).

3. M5S is all over the place ideologically; it is hard to place on a left/right spectrum. But many of its policies are those that people in Green Parties in other countries would support. The "five stars" refers to the following 5 areas of concern: public water, sustainable transport, sustainable development, right to internet access, and environmentalism. More generally, they are against the caste of professional politicians and celebrate amateurism and bottom-up direct democracy. Key party decisions are made by vote over the internet.

4. M5S is against the Euro (although they favour a referendum on the issue of leaving the Euro) and against immigration; and joined the same group in the European Parliament as UKIP.

How would I vote?

Yes to the Referendum--if only because I consider Grillo another Farage/Trump type and would be loathe to do anything to give aid to the forces of populism. There is also the danger that the markets will react badly to a No vote. Simon Nixon (WSJ) envisages this as a worst-case scenario:

"A defeat for Mr. Renzi would lead to a period of political instability. Mr. Renzi could follow through on a pledge to resign or be forced into a new coalition until elections are held in 2018. Either way, markets would interpret his defeat as proof that Rome is incapable of reform, raising doubts about Italy’s ability ever to deliver the kind of growth needed to put

its debt burden of 135% of gross domestic product on a sustainable footing."

I don't think that the problem in Italy is one of law-making. (Indeed, Renzi's government has been very successful in enacting laws, see

this scholarly article for an assessment of Renzi's legislative record.) Nor do I think that the present political system rules out economic and political reform. Obstacles to reform lie elsewhere in what is a very conservative society.

In short, Italian governments have legislated in recent years many far-reaching laws aimed at reforming their dysfunctional politico-administrative system. The problem is that these laws are rarely successfully implemented. The Italian political system suffers, in short, from too many "veto-players." (For a brief discussion of this concept in Political Science, see

the work of George Tsebelis). For a good news article on this problem in Italy,

see here.

Supporters of YES, however, claim that these constitutional reforms actually will help implementation, if only because it will no longer be necessary to gain the approval of 20 Regional Governments to pass major legislation. Furthermore, they deny that there is any genuine fear that the reforms will precipitate an overly-centralized state vulnerable to a fascist-type leader (a veritable obsession of people on the NO side). Italy will still have a Constitutional Court to check abuses of power; and people will still have a vote to toss out potential dictators.

All of these points are well made by Pietro Ichino (a labour lawyer and a senator who supports Renzi) in his reply to (what he calls) "the nonsense" expressed by The Economist's case for a NO vote (see below).

As Ichino puts it (my translation):

"The real threat to Italian democracy doesn't seem to be that of a slide towards dictatorship, but rather that of inconclusiveness--a politics of inconclusiveness that gives birth to "anti-politics."

It is no coincidence that the Mayors, who are elected by a majority system....similar to that of the "Italicum" [i.e. the voting system that gives a bump in seats to the majority party] are now the most popular politicians, the most loved by Italians. The Mayors are responsible for the implementation of their own programs. If they do not succeed, they cannot say that they were prevented by this or that."

WHAT IS LIKELY TO HAPPEN?

Fresh from my success in predicting the outcome of the Brexit referendum and the US Presidential elections, I predict the NO vote will win quite substantially.

And then the following will happen:

(i) Markets plummet--esp European bank stocks, but also the Euro--probably towards 1:02/1:03; and the Italian bond spread will worsen.

(ii) Renzi will announce he is resigning;

(iiia) The President will ask Renzi to stay on for the good of the country;

or (iiib) The President will ask Padoan to form a new Government;

(iv) Markets will slowly recover but Italy's bond spread will remain "stubbornly high."

(v) M5S will win the next election.

READINGS

Here are some preliminary topical articles on the Referendum to read:

A Berlusconi and Trump Comparison (and

another here and

here)

Silvia Merler,

The Italian Referendum (check out the links in this too)

Interview with two Italian Experts including

the Former Head of Constitutional Court

Lorenzo Codogno,

Italy's Constitutional Referendum

Italy's Constitutional Reform,

The Economist (a surprising endorsement of the No position)--for a critique of this article, see Chris Hanretty response

here and (in Italian)

Pietro Ichino's response (I quote a bit of this above).

Mario Monti's (former technocratic Prime Minister and now lifelong Senator) view (another surprising endorsement of the NO position):

On December 4, Italians will vote in a

referendum on a partial reform of the constitution. Unlike the decision of British premier David Cameron to hold the

Brexit referendum, there was nothing reckless about Prime Minister Matteo Renzi’s calling of this one.

Under the Italian constitution, any change to its text is subject to approval by referendum unless parliament approves it with a two-thirds majority in both houses. Mr Renzi’s reform did not win such a majority, unlike the previous amendment adopted in 2012, which introduced a requirement for a balanced budget over the economic cycle.

Where

Mr Renzi has taken a wholly unnecessary risk is in putting his own political future on the line. It is this defiant position — boldly asserted at the beginning before being watered down somewhat — that is exposing Italy, the markets, and some even say the eurozone as a whole, to considerable uncertainty. Is December 4 referendum day or is it an election day in disguise?

There are two distinct issues here: on the one hand, the merits of the proposed reforms; on the other, those of the prime minister himself. To mix them up is an abuse of democracy. For the record, I will be voting No in the referendum. But I see no reason for Mr Renzi to stand down if No prevails.

I will vote No because the disadvantages of the

new constitutional measures outweigh the advantages. In particular, the new rules on co-operation between the chamber of deputies and a reformed senate in the passing of legislation is likely to make the whole legislative process more cumbersome and unpredictable, not less.

Further, consider the fact that incompetence and corruption have for many years now been problems primarily at the regional and local level. For this reason, I am concerned by proposed changes to the senate that would see its members nominated by regional parliaments, and drawn from members of those bodies and from among the mayors of Italy’s biggest cities.

As for Mr Renzi, there is nothing, in terms of law or tradition, that would require him to resign in the event of his reform being rejected. Mr Cameron did resign after the Brexit vote, but he had thrust his country into an unprecedented crisis after having called an unnecessary referendum. But neither French president Jacques Chirac nor Dutch prime minister Jan Peter Balkenende felt compelled to step down in 2005 when their voters rejected the European constitution that each had signed on behalf of his country.

Should Mr Renzi decide to stand down in the event of a No vote, the responsibility would be his alone. And any turbulence in the financial markets would have to be attributed not to the referendum result, but to two factors for which the prime minister is responsible. First, his personalisation of the referendum campaign. And second, to the way his emphasis on that campaign has hampered the implementation of reforms needed to stimulate economic growth. Of particular importance are structural reforms designed to address the severe problems of a number of

Italian banks and the completion of budgetary consolidation before the unusually favourable circumstances of the past few years come to an end.

Whatever happens on December 4, I hope Mr Renzi stays and resumes with renewed energy the job he has left half-finished. However, if he were to leave, I do not believe that there would need to be an early election, let alone the installation of a technocratic government. Instead, the president, Sergio Mattarella, could ask someone from within the current government to form a new one until the next election in 2018.

Financial markets need not get excited. After all, Italy is the only southern European country to have emerged from the crisis in the eurozone without external assistance.

Perhaps the bleakest assessment of Italy's immediate prospects comes from

Ambrose Evans Pritchard (an arch Brexiteer and Europhobe). AEP fears the ending of QE (ECB bond buying, in short) more than the referendum results. The key bit of his argument is here:

"The

global reflation shock since the election of Donald Trump is bringing matters to a head faster than anybody could have imagined weeks ago. Italian borrowing costs have risen in lockstep with US Treasury yields, even though Italy is not reflating at all and is certainly not about to enjoy a fiscal shot in the arm.

Italy is in a sense the biggest casualty of the Trump effect and the tornado of imported monetary tightening. Its banks own €400bn of Italian government bonds and these are suddenly worth less. Some paper losses must be marked to market, further eroding core capital ratios.

It is our old friend the 'doom loop'. The banking crisis is driving up sovereign bond yields, and higher yields are in turn driving the banks into deeper trouble.

The painful saga of Italy is by now well-known. The country is stuck in a depressionary debt trap. Trend growth is below zero. GDP is still 9pc below its pre-Lehman peak. Industrial output is back to levels reached thirty-five years ago.

The contours are worse than the 1930s. It is a lost decade turning into a second lost decade. No large developed country in modern times has ever suffered such a fate.

Italy is the victim of a vicious cycle of labour hysteresis as economic stagnation and weak productivity reinforce each other. Its exchange rate is overvalued by 20-30pc against Germany.

How easily we forget that Italy used to run a big trade surplus with Germany in the old days of the lira, and its real growth rate tracked German growth almost exactly with the help of devaluations."

Note: not all economists agree with the claim that Italy can recover with "the help of devaluations." See the exchange between

Martin Sandbu (an elasticity pessimist) and

Paul Krugman (devaluation will solve the problem).

THE HISTORY OF ITALY"S PROBLEMS

In order to understand the broader historical context that led to Renzi, it is necessary to understand the failures of Berlusconi and the German concern about Italy under Berlusconi's misrule.

The following series of articles in Der Spiegel from 2011 are especially useful here:

The Sweet Poison of Berlusconi: Italy's Downward Spiral Accelerates and

here and

here and

here and

here and

here

Perry Anderson, who is both a Marxist and a misery-guts, has written a couple of very long but perceptive analyses of Italian politics over the last 20 years.

Perry Anderson,

The Italian Disaster LRB (2014)

Perry Anderson,

Land Without Prejudice LRB (2002)

Some long and short news documentaries of the key political figures in recent Italian Politics

Matteo Renzi (2014)--

John Mauldin, "When Hope is a Strategy"--a very interesting discussion of Italy's economic problems with lots of charts and an assessment of Renzi's ability to solve these problems.

Beppe Grillo (2008)

Beppe Grillo (2010)

For a bunch of scholarly articles on Grillo's M5S, see the Special Issue of

Contemporary Italian Politics Volume 6 2015 (available online from the library); see especially Paolo Natale,

"The Birth Early History and Explosive Growth of M5S"

Rachel Donadio Talk on Italy 2013

Berlusconi (BBC Documentary 2010) (

see all parts here(2) and

here(3) and

here(4) and

here(5) and h

ere(6) and

here(7)

Berlusconi

(BBC DOCUMENTARY 2010)

The Last Days Of Silvio Berlusconi (2011)

Silvia Berlusconi and the Mafia

(in French)

Girlfriend in a Coma (Bill Emmott--former ed. of

The Economist. I have the DVD if anyone wants to watch the whole thing.)

Italy's Productivity Blues

Francesco Giavazzi Lecture (2013)--

Italy's Future--Reform or Decline

--Giavazzi makes the interesting observation that Italy's output in 08/09 fell more than in other countries which experienced (unlike Italy) a housing bubble and a bank crisis (Spain, for example); and then recovered at half their rate in 10/11. He notes that no one has adequately explained this puzzle.

--Giavazzi offers four explanations for why Italy has stopped growing:

(i) The Size/Inefficiency of the Public Sector;

(ii) The Euro (unit labour costs rocket compared to Germany)--

(iii) Firms are too small, too family-run, and drawn to protected service sector.

(iv) Failed Transition from Imitation to Innovation (why is there no Apple and Facebook?)

In short, Italy suffers from too much economic activity in the unproductive sector and not enough in the productive sector.

Politics blocks any effective transition from the former to the latter.

Luigi Zingales Lecture on Italy's Economic Problems--

slides here

Zingales' Conclusions:

1. The Italian disease appears to be an extreme form of a European disease:

2. This disease appears to be linked to the lack of meritocracy and professional performance-based management.

3. Inability to take full advantage of the ICT (basically the internet and computers) revolution–

4. We still need to explain why these practices are so rare in Italy and Southern Europe

5. Suppose that there is some institutional factor in Southern Europe that makes difficult to keep up with technological change.

6. Since Japan and the United States could never have maintained a fixed exchange rate from 1950 to 1990? [Why? Because Japanese growth rates were at least twice those of the US in that period], then it is no surprise that Italy could not live in a common Eurozone with faster growing Northern European countries.

7. Italy cannot survive in the Euro as presently constituted.

Two comments on Zingales' talk:

1. Even if he is right, the talk begs the question

why Italy was never able to implement a more meritocratic political and administrative culture. Why did Italy fail where France and Germany succeeded? To answer this question, one needs to look more deeply into Italian history and the nature of

the Italian family and

localism.

2. So far as the Euro is concerned, there are three options:

(i) Fix it through centralization--turn the EU into a Superstate, a United States of Europe (

my own preference);

(ii) Muddle-through--(although this presumes that the Germans will be willing to support more bond-buying);

(iii) Break it up--whether into two groups (NEURO/SEURO) or one big Northern group and the rest (NEURO and the rest) or a Europe of national currencies.

Since (i) is not likely to happen; the choice is really between (ii) and (iii)--my preference would be (iii) over (ii), which condemns Italy (and other Southern European countries) to years of economic misery and unemployment.

The trouble with (iii), however, is that it is far from clear whether devaluation will work--here we are back to the elasticity pessimist thesis discussed earlier--see Maria de Merzis,

The Italian Lira for more on this.

The Social and Economic Background to the Crisis:

Italy has Horrible Demographics